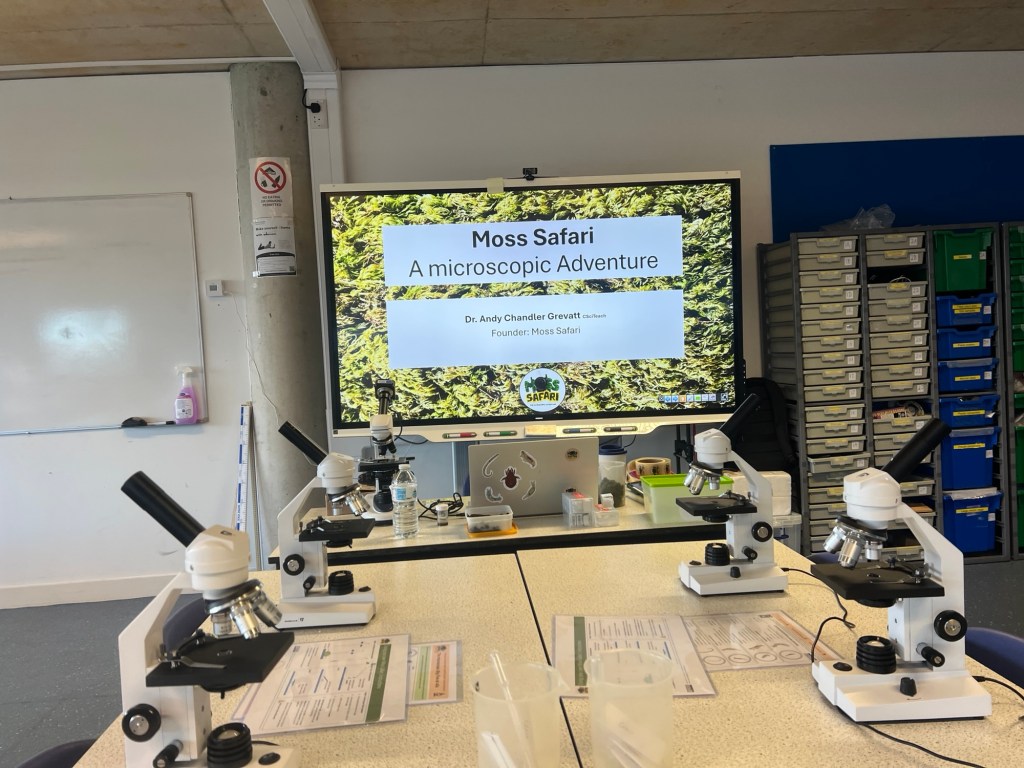

I think this is the seventh year I have run Moss Safari with my trainee science teachers, and it is always a highlight of my year. I always learn something new, and I always come away thinking about Moss Safari slightly differently.

This year felt different.

Moss Safari has taken on a life of its own. With the book now out and some trainees already having experienced Moss Safari in their placement schools, a few arrived already knowing what it was. That alone felt quietly astonishing. Something that began as a way of slowing down and really looking at moss is now travelling beyond me.

Despite that familiarity, what mattered most this year was not recognition or naming. It was discovery.

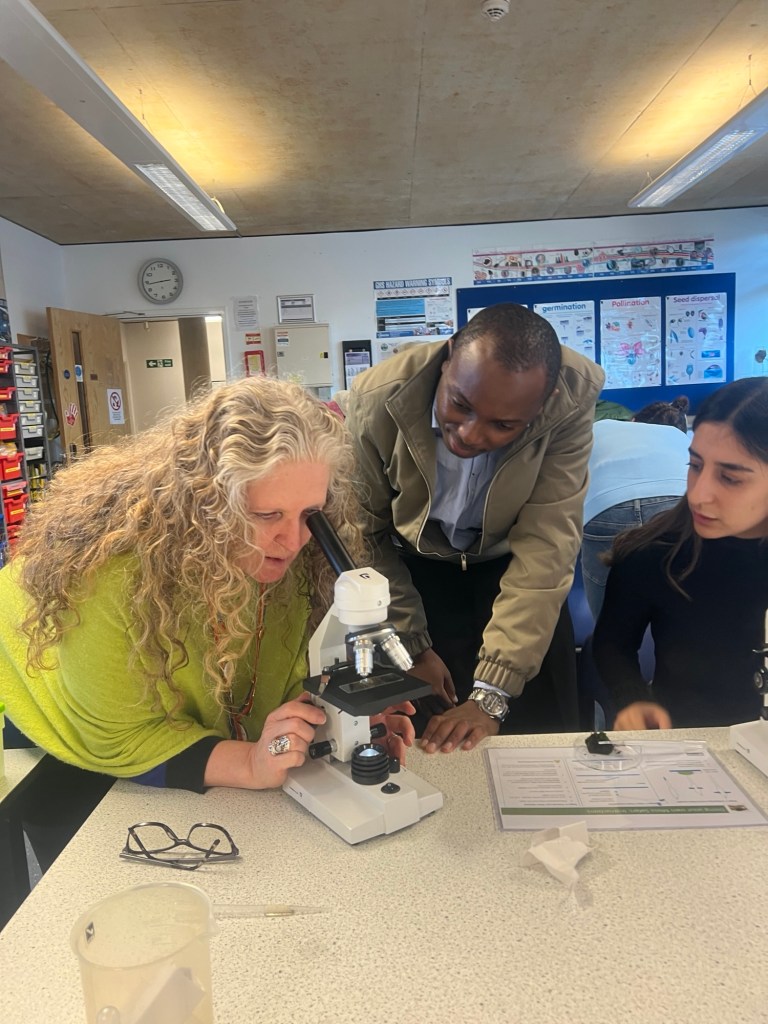

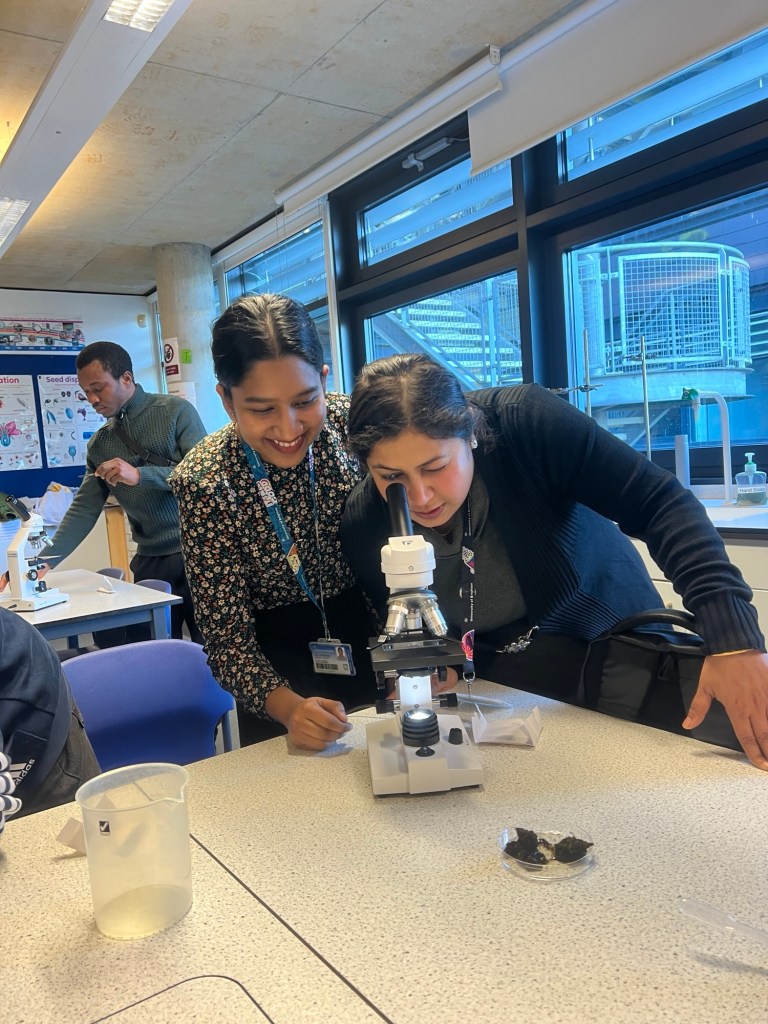

First contact under the microscope

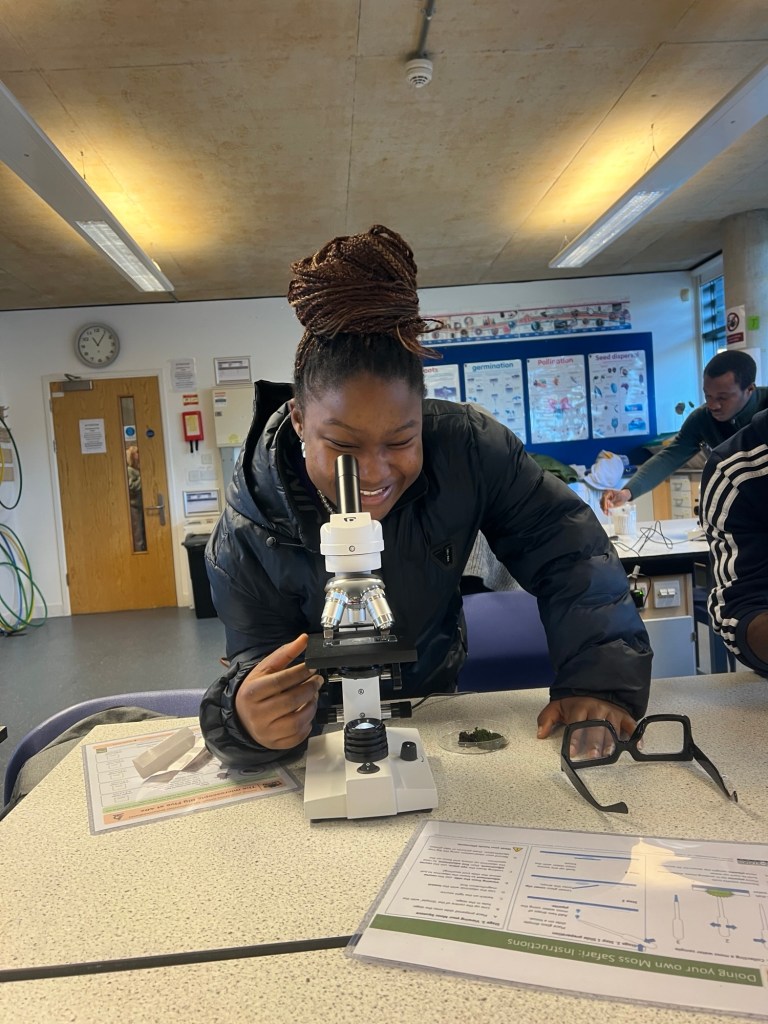

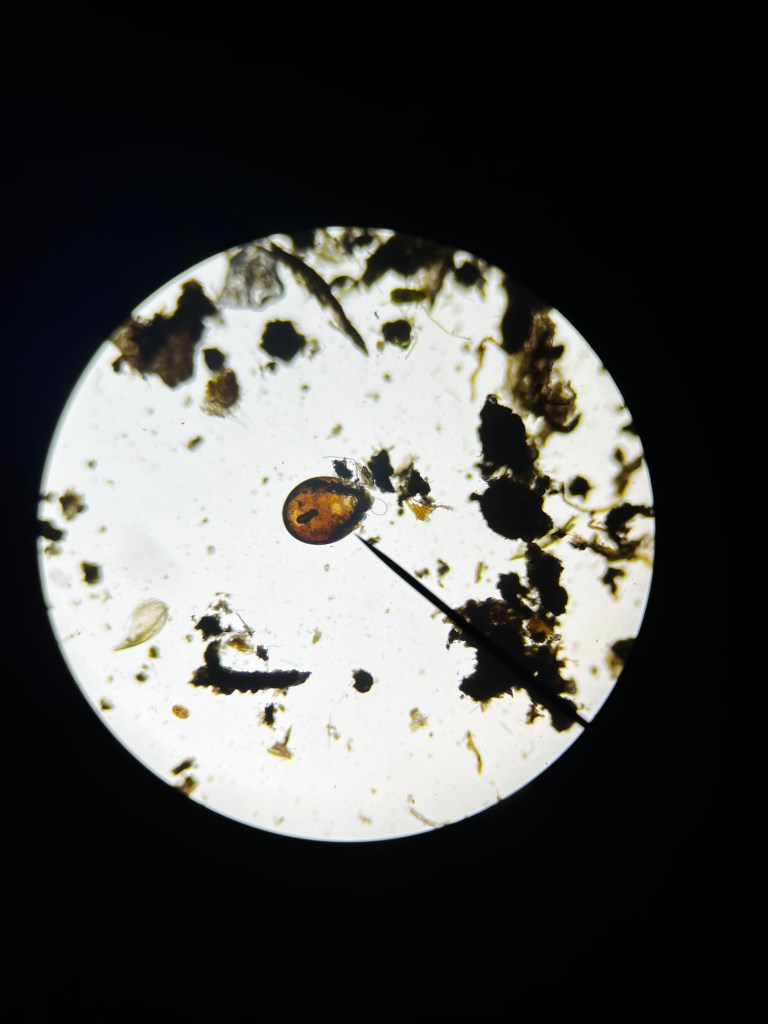

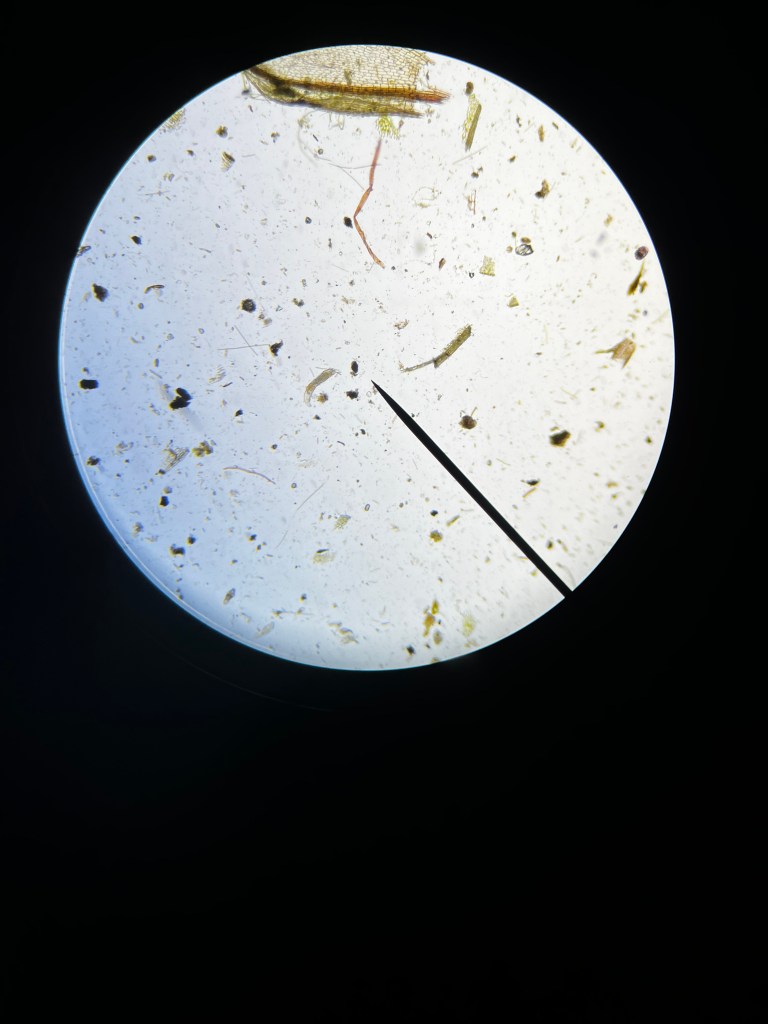

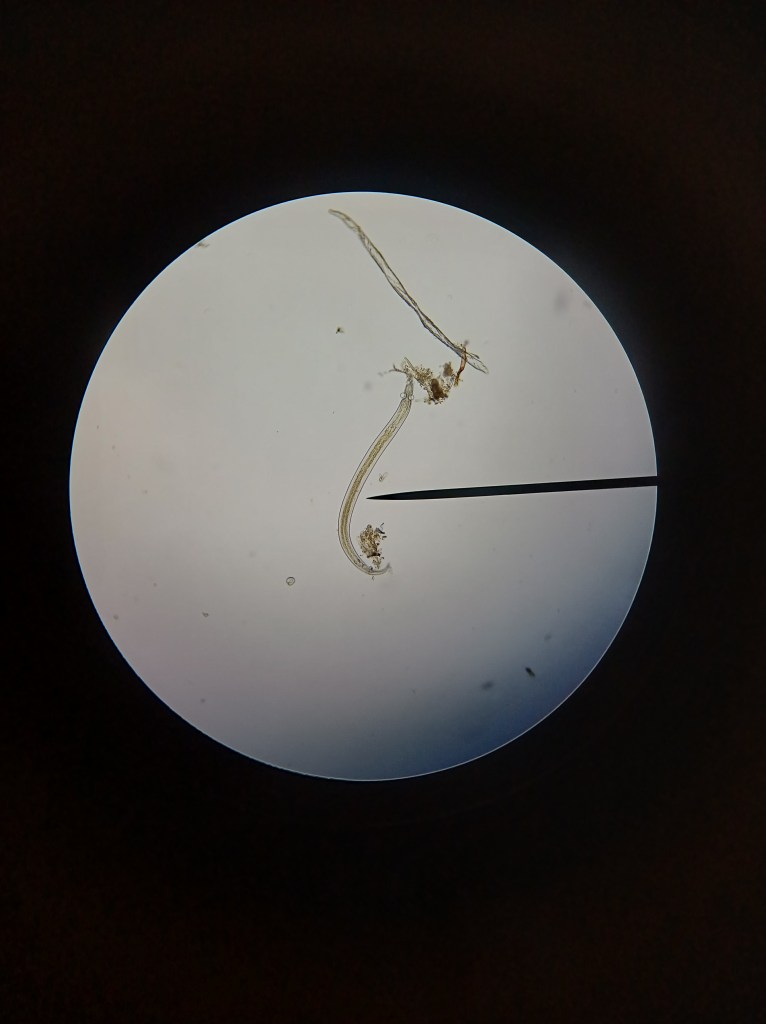

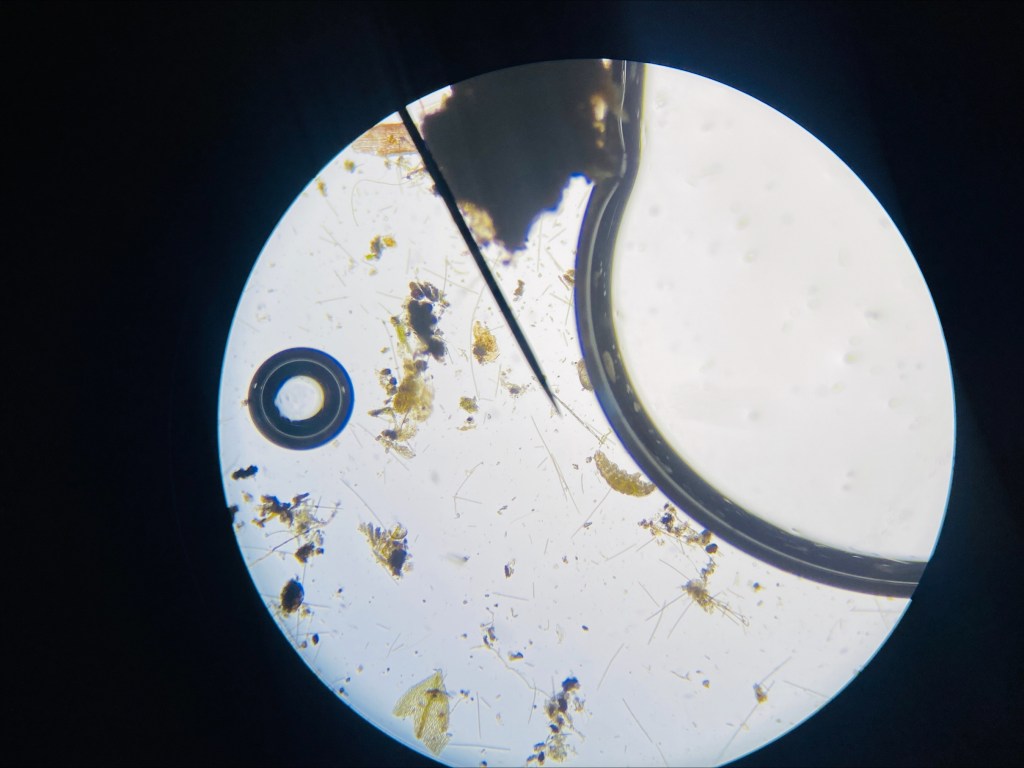

We talked explicitly about what it means to be the first person to see something. Not necessarily historically first, but personally first. That moment when you focus the microscope and realise you are looking at a living animal that you have never encountered before. No label. No checklist yet. Just movement, shape, behaviour, and the question, what on earth is that?

I asked the trainees to imagine trying to communicate what they were seeing to someone who had never looked down a microscope. How would you describe it? How would you persuade someone else that this strange, wriggling, gliding thing was really there?

We also played with the idea that perhaps these organisms did not have names yet. What features would matter? What would you notice first? What would you ignore?

This idea of observation before identification sits at the heart of Moss Safari. Names can be useful, but they can also shut down curiosity if we reach for them too quickly. Discovery thrives in that uncertain space where you are still figuring things out.

What the trainees told me

I did the introduction to Moss Safari, contextualising it within Science Capital, extra-curricula learning and enrichment in science education. FRom the feedback, I am able to understand what the trainees took away from Moss Safari.

One hundred percent agreed or strongly agreed that the session was interesting, enjoyable, and that they learned something new. Over ninety percent said the session inspired them to try Moss Safari themselves, and to use it in their teaching. More than eighty percent agreed or strongly agreed that the session made them consider buying a microscope. That feels like a small but significant indicator of a shift, from seeing microscopy as something institutional to something personal.

The written comments reveal where that shift came from.

“Getting to explore things that cannot be seen with the naked eye.”

“Finding the little creatures in that small slide.”

“Seeing a giant ecosystem in a pipette of water.”

Others focused on specific encounters.

“Seeing living organisms like nematodes clearly was amazing.”

Several simply celebrated discovery itself.

“Discovering things I never knew.”

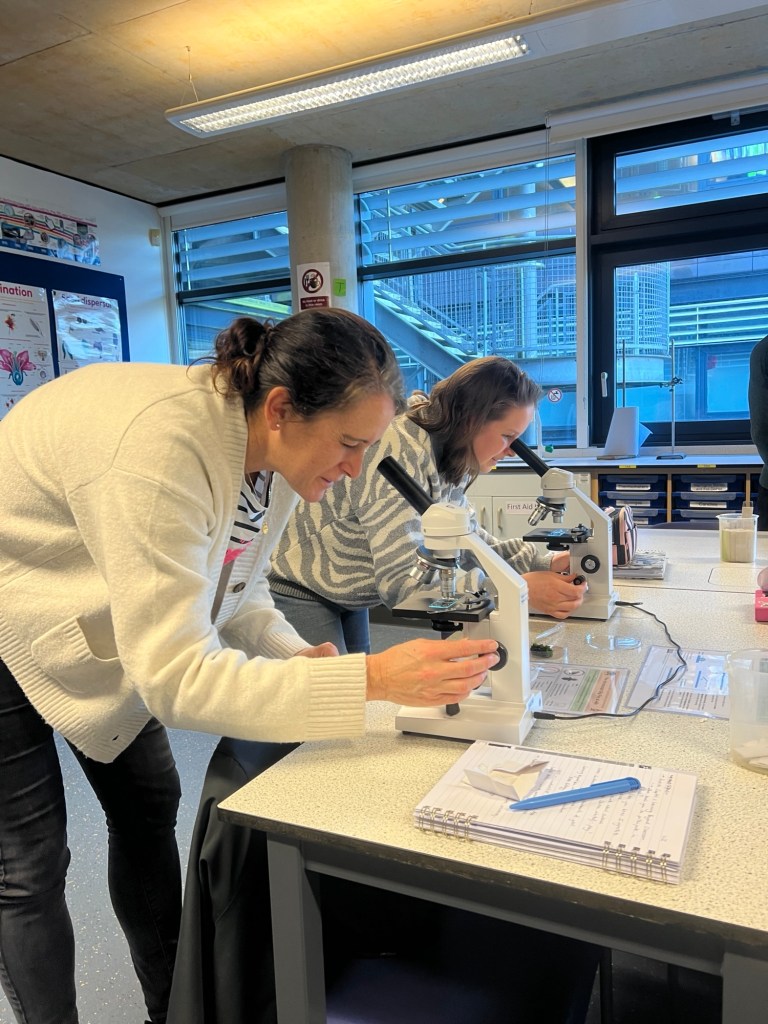

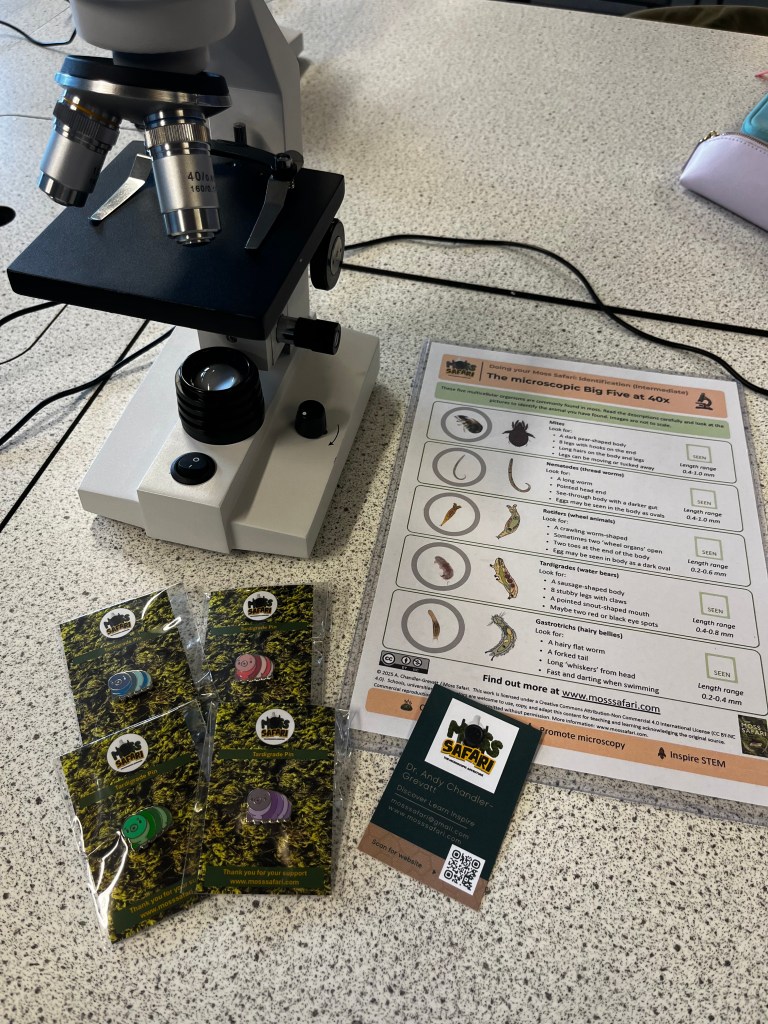

Structure without shutting down curiosity

The Big Five checklists were described as very or incredibly useful, but not because they gave answers. Instead, trainees talked about confidence and focus.

“Great visuals and clear descriptions.”

“It guides me with what the structure should look like.”

“They are like a field guide for a tiny ecosystem.”

That balance matters. Enough structure to support observation, but not so much that it turns the experience into a tick box exercise.

Reconnecting with nature through a lens

There was also a strong sense of reconnection with nature. Most trainees said the session helped them connect with nature to a great or very great extent.

“Definitely felt connected with nature.”

Several commented that they would never look at moss in the same way again.

Perhaps my favourite comment captured the ethos of Moss Safari.

“A fantastic exercise that is incredibly accessible.”

Moss Safari is not about rare places or specialist environments. It is about first contact. About encountering living systems that are already all around us, but usually unnoticed. It is about learning how to see, how to describe, and how to communicate discovery before we rush to name it.

Seven years in, that moment of first contact still feels fresh. And judging by the feedback from this year’s trainees, it still does exactly what I hope.

Acknowledgments

Piper, our technician for setting up and clearing up.

Sarah Poore and all the University of Brighton Science Trainees

VITTA Education: Microscopes