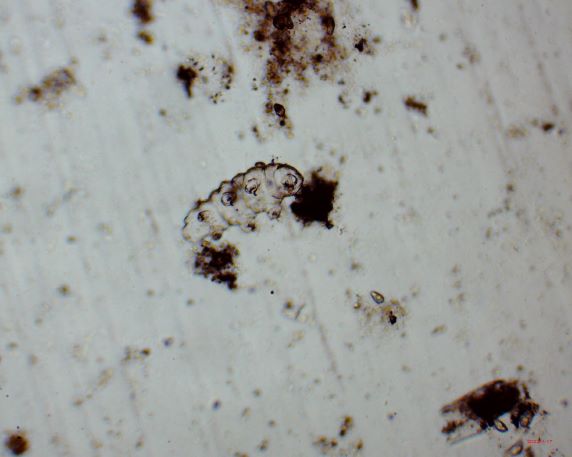

Imagine my surprise when doing a Moss Safari, always hoping to see a living, moving tardigrade, but instead being confronted by mysterious tardigrade ghosts (figure 1). What are these strange apparitions? Am I so desperate to find tardigrades I am imagining them? Clearly not, there is a sensible scientific explanation.

These tardigrade outlines are in fact the shed skins of tardigrades. Like many invertebrates, tardigrades shed their skin as they grow. These shed skins are called ‘exuvia’. As they grow, tardigrades moult, leaving their exoskeleton behind. In fact, it has been found that some species of tardigrade make good use of their exuvia.

I have done some reading about the mysterious life cycle of the tardigrade. Despite having first observed tardigrades mating back in 1895 [1], it is only over the past two decades that we have started to understand their life cycle and mating behaviours more fully. In general terms it seems that when active, tardigrades can produce a new generation every couple of weeks [2].

Tardigrades hatch from eggs. Sometimes these eggs are laid in the environment, but some species lay their eggs inside the exuvia.

Eggs take a few days to hatch, often less than a week. Species who lay eggs in the environment have eggs with spiky shells, those who lay eggs in exuvia, have eggs with smooth shells.

Juvenile tardigrades mature into adults within 14 days, when they, themselves are ready to lay eggs.

Now, hold on there, skip back a little. Some species lay their eggs in exuvia. This reminded me of an anomaly (to me) I observed a couple of years ago. Looking through my photographs, I have actually found such a thing – an exuvia with eggs in it (Figure 3).

So, why would tardigrades do such a thing? I haven’t found anything in writing, but I am willing to bet that it is for protection from predators, maybe even protection from fungi and bacteria. May be the spiky eggs laid freely in the environment have the spikes as protection in the absence of exuvia protection.

Watch this space.

References

[1] Sugiura, K., & Matsumoto, M. (2021). Sexual reproductive behaviours of tardigrades: a review. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, 65(4), 279-287.

[2] Tsujimoto, M., Suzuki, A. C., & Imura, S. (2015). Life history of the Antarctic tardigrade, Acutuncus antarcticus, under a constant laboratory environment. Polar Biology, 38(10), 1575-1581.

Correct me if I am wrong

I am learning all the time. I am am amateur hobbyist who enjoys doing light microscopy of organisms that inhabit moss. If you notice a mistake, let me know. I am always willing to correct and learn.